I thought being stuck in Dallas Fort Worth airport for five hours would make me want to finish up my last assignment, sadly it did not. Instead I became fascinated with all the people sitting, standing, and running all over the airport. Everyone was so different, going different places, seeing different people, telling different stories. I could tell by the whispered conversations next to me, hugs and kisses across from me, or worried looks passing by me that every person had a purpose for their travel.

My airport experience reminded me a lot of my farm experience. Full of so many stories and many purposes. I learned so much in Iowa. I met some pretty awesome people. Most importantly I learned a lot about myself.

Farming is a special craft, and it may be a craft that is dying. Similarly so are all the small rural towns that make up Iowa’s landscape. Because consolidation and increasing markets farm has changed. Instead of communities where every home may have a couple of acres of land to farm, there are now vast amounts of land in between the few scattered homes that have managed to survive the ever-changing farm market, nearly destroying the communities that can barely manage to supply students for schools, keep open post offices, or have places to shop for groceries.

Going into the trip I thought I would be on the side of the farmer who manage and tend to these huge operations, but over time I learned that these big agricultural operations weren’t helping the small communities. After coming to my realization I wanted an answer. I wanted so badly for someone in one of the many presentations we went to give an answer, but they did not. Like many problems I learned there is no single solution. Furthermore, I learned that farming is not equitable. For the people still holding on to their small operations there were less opportunities for them. For the people who just do animal agriculture there were less opportunities for them. For the people who do organic farming there was less opportunities for them.

Even though farming in Iowa seems to be producing more and more yield, there was less and less for the farmer. Where is the equity?

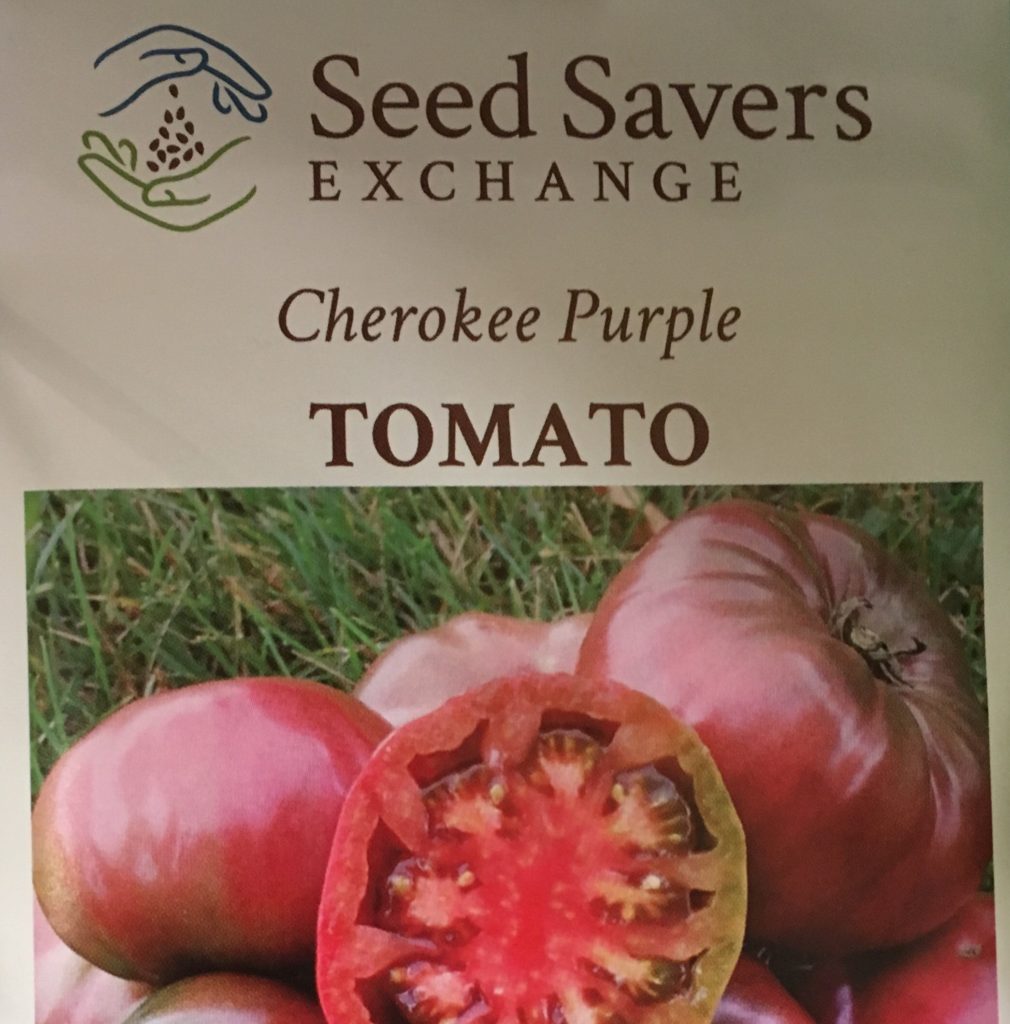

I don’t know, and I don’t know if I’ll ever find it. I do know that I appreciate everything I consume as a consumer. I know I want to uplift and support small communities in my home state. For every farm there is a community behind it and we should invite people from the community to explore these farm spaces to investigate exactly where the food comes from.

Iowa opened the complexities of farming to me and showed me how important my role as a consumer in. No matter what you believe the right way to produce food may be, has consumers who have access to many food options we can support what ever farming style best fits us. Continued education will help me decide what food sources to support and can also help figure out how to make all the food options accessible to everyone, especially the communities where some this food directly comes from.

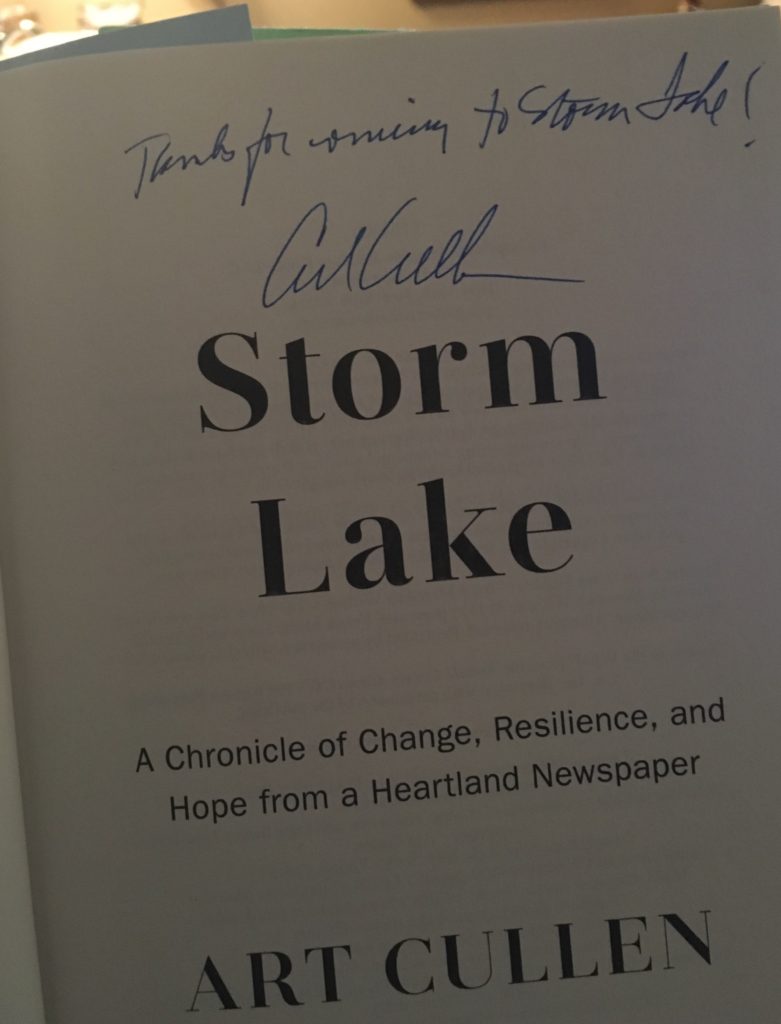

This may be might last blog about Iowa, but I feel pretty confident that this trip won’t be my last time visiting Iowa. There is a space for me there that I didn’t think I would discover.

Thank you Iowa, for the bees, for the food co-ops, and the cows…especially the cows.